In retrospect

The journey of 1963 was for me an eye-opener to Europe’s recent history, a stimulant for a process of exploration by study, conferences and travels. To observe how Europeans turn a blind eye to their past in its double role of Prometheus and Hermes, is both painful and fateful. They seem to prefer to stand with one foot in the Mosaic legacy and with the other foot on the moon, instead of in the common heritage of Prometheus and Hermes.

Prometheus without Hermes is dangerous, but so are Narcissus or Dionysus. A god, like a child, should not be left alone when he or she plays. The warning thrown out by Nietzsche in Die Geburt der Tragödie (The Birth of Tragedy, 1872) – namely that a civilization should not cultivate one god-figure only, but at least two (like Apollo and Dionysus in pre-Socratic Greece) – has shown itself even more incontrovertibly true than one had thought.

Mythological Europe Revisited, Antoine Faivre.

Austria’s Alpbach Conference Centre

In 1955, Austria became a state with the official status of neutrality vis-à-vis the occupying powers in Berlin and elsewhere. It meant that the Russians, the Americans, the British and the French withdrew their troops from its territory. Situated between Europe’s East and West, Austria’s Alpbach Conference Centre hosts conferences that foster the dialogue between various cultures, notably Asia and Europe. With a letter of recommendation by Jacques Presser, my professor in modern history, I acquired a modest stipendium of the University of Amsterdam to participate in an East-West Conference in 1966.

I will never forget the lectures by Sarkisyan and Dumont, director of the College of Europe in Bruges, and their intense debates about the Cultural Revolution in China. I finally sided with Sarkisyan who defended the thesis: one has the right to bread but not the duty to bread, attacking the politics of the forced mass labor camps in China.

T.M.P. Mahadevan from Madras and his Indian Maoists colleagues from Calcutta in the North of India, couldn’t differ more in their manner of philosophizing and political views. Mahadevan’s lecture about the metaphysical notion of ‘One’ impressed me deeply. Never before did I hear the notion so clearly and convincingly presented.

Those who deny the importance of metaphysics by reducing its meaning exclusively to history as the Maoists do, don’t realize that they provide history with a metaphysical status.

The East-West Conference

The Conference had awakened my interest in Asian philosophy. Gradually, it changed my orientation on Western philosophy, only to discover that the Greek-Egyptian gnosis and Indian metaphysics share a similar endeavor for a knowledge that’s healthy for body and mind, and for the individual and the community at large. Both philosophical traditions perceive cosmos and life as a whole.

Travels in Central and Eastern Europe

During the summer, we travelled with our children within Europe: to the North and South, but also the East. The confrontations at the borders of the Warsaw Pact could be fun, when – at Bulgaria’s border – an officer was ‘reading’ the children’s book Jip and Janneke upside down. But Prague, 1968, was different.

A twofold effect

The Conference had a twofold effect on my style of thinking. The tough yet open-minded debates were dialogues in the sense that not power or authority has to be decisive, but insight into the meaning of ideas and their hidden values. The experience had a liberating effect. Never before did I feel such a close and intimate relationship between theory and praxis. If you turn your theory into praxis, something I did by nature or character but mainly unconsciously, it becomes manifest how crucially important theorizing is. Philosophy lost its last vestiges of innocence. Hegel’s philosophy of history still lingered in the back of my mind, after I wrote about it under the guidance of the Hegel-expert Jan Hollak. The question arose how to view the different Marxist and Maoist interpretations of Hegel. The Marxists continued Hegel’s dialectical logic but upside down: mind became matter, and matter mind. And there was Mahadevan, dissolving the Gordian knot between mind and matter by showing: it is our mind that causes the problem! ![]() Mythological Europe Revisited, Grazia Marchianò.

Mythological Europe Revisited, Grazia Marchianò.

Prague

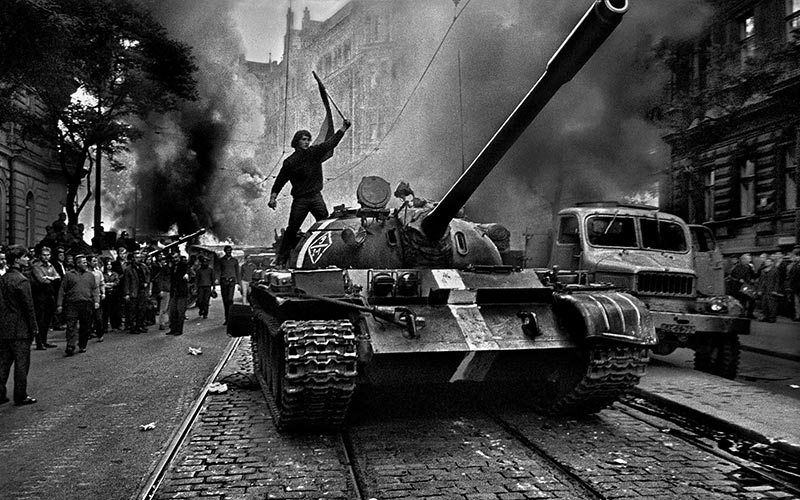

Leonid Brezhnew and his allies decided to quell the Prague Spring, afraid it would spill over to other countries of the Warsaw Pact. The May revolt of 1968 in Paris, Amsterdam and other cities in the West, didn’t miss its effect on the citizens of Prague. When the Russian tanks arrived, the young people changed the traffic signs in order to create chaos in the best tradition of soldier Schweik. The appearance in the streets of Prague of huge Russian tanks, looking like amphibious monsters with their little windows, was scary. When I knocked on one, the shutter went open and a Russian soldier looked at me, while I looked at him. I suppose that the guy hardly knew where he was. The next morning the tanks had gone as if they had disappeared into thin air. But in the evening there they were again. It was frightening. I drove with such speed from Prague to Amsterdam that I destroyed the motor of my Saab.

The next day, a few journalists of De Groene Amsterdammer met in Café Scheltema to discuss the situation of the invasion. Sem Dresden told his colleagues: “Keep it cool!” He was afraid of a heavy, anti-communist reaction.

Berlin, a divided city

In 1961 the Iron Curtain, a phrase by Winston Churchill, became a physical Berlin Wall that divided the city in an Eastern and Western part. Berlin became the urban embodiment and symbol of two ideologies and two completely separate lifestyles, with the USSR, Warsaw-Pact and allies in the Eastern part of the city, and the USA, NATO and allies in the Western part. A corridor through the communist DDR connected West-Berlin with the capitalist BDR.

The stalemate between both camps had one advantage: the use of nuclear bombs became too dangerous for either side. Peace remained – if we may use this euphemism – by sheer nuclear terror. If not, the chance that nuclear bombs had been dropped on Vietnam, Cuba or elsewhere, as on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, can’t be excluded.

The Wall and the Balloon

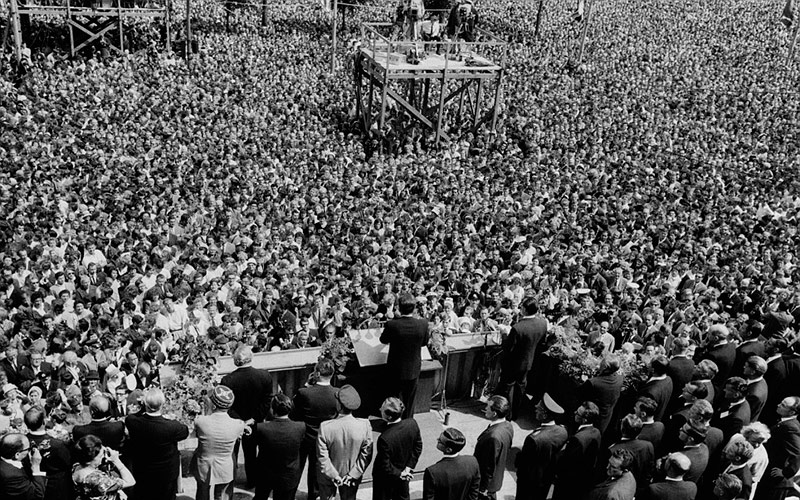

I joined a cultural visit to West Berlin, organized by the Amsterdam Circle for the Arts (Amsterdamse Kring voor de Kunsten) and the Ruigoord Community. We travelled by bus, a very old one, to Berlin. At the Marianne Platz we put up our tents, to explore from there the city during day time and to tell each other stories at night. The Marianne Platz was close to the place where on June 26, 1963 John Kennedy spoke his famous words: Ich bin ein Berliner. The effect of the four words in German cannot be overestimated. So, we wanted to do something special. The Ruigoord friends had brought their liquid gas to fill huge balloons which could drift from the Western side of the Wall to the Eastern side. I suggested to write 1 x 1 = 1, as follows. The first 1 in green; the second 1 in red, and the equalizer 1 in fat brown, arguing that the color brown was the synthesis of the colors green and red: green for West Berlin and red for East Berlin, while brown referred to their common Nazi past. It was a bridge too far, and for rather good reasons.

The encounter between the Vopo and the Artist

West Berlin developed a rich, cultural life, receiving many subventions to keep the city alive. Authors, intellectuals or artists like my friend Richard Hefti travelled to Berlin regularly. Richard was a member of the Berlin sister of the Dutch BKR (beeldende kunst regeling – visual art regulation). Berlin bought paintings and drawings of visual artists, once they became a member. Travelling by train through the corridor in East Germany to West Berlin, he worked at his painting in the last carriage of the train, when a Vopo checked his papers. The man looked at him and asked what he was doing. “Well”, Richard said, “I am painting. Tomorrow in West-Berlin, I get …marks for the painting but it has to be dry”. The man looked at him with eyes like billiard-balls. The frame was dripping with paint, and the price of the painting equalled his monthly salary.

The encounter between the Vopo and the Artist illustrates the surrealistic reality of Europe in those days. And something similar is happening again. Today’s capitalism starts eating its citizens to get its money back. The Vopos reappear but in disguise. History repeats itself all the time but always different as if it wants to prevent people seeing that changes take only place at the surface, not in the deep structures of their reality.

The Wall, a catalogue and a peeing boy

The exhibition Tendenzen der Zwanziger Jahren in 1977 in West Berlin had a huge political impact. Presenting all the art disciplines, architecture and urban design, including the USSR, we wanted to visit the exhibition. Everyone expected that members of the RAF (Rote Armee Fraktion), a leftwing German terrorist group of the 1970s, would risk visiting the exhibition, where – for obvious reasons – the secret police was present. After the visit, in the possession of the huge catalogue, we crossed the Berlin Wall from West to East in our van. During the border control, an officer ‘confiscated’ the catalogue; I got a stamp in my passport after it had been sealed. I would get it back when we returned to West Berlin. When we did, our son Job had to pee. He left the car peeing against the Wall. A Vopo took a picture, while his colleagues ordered me to station the van above a huge mirror on the ground. They looked in the mirror to check that nobody was hanging under my car to escape the DDR, the communist version of paradise. Vopos taking pictures of my son and Vopos looking under my car, all with serious faces. After getting my catalogue back, we had to stop at the Western border. Here the officers were only interested in drugs. I was left with one conclusion: communists are interested in books and perhaps in young boys peeing; capitalists are interested in drugs.

Czechoslowakia, once more

In 1972, after participating in Linz in a conference named after Bertrand Russell, we left the city for the Czech border with numerous copies of the lectures and some books, among them Analyze – Decondition, an introduction into systematic philosophy.

The officer at the border didn’t have a pleasant expression: he tried to copy Joseph Stalin. After checking the luggage, he ordered me to bring all papers and books to his counter, including Analyze – Decondition. He sealed the copies, took the book, and asked: what is it? I said: a cooking book. He didn’t answer, took the book and added it to the ones which were sealed already. I took it back, and said: Marx taught us that every laborer has the right to his own work; well, this is my work, so I have rights. This time, it became a bit serious. A writer from the West who quotes Marx must be a dangerous man. Moreover, with my beard and long hair I had the look of a narodnik from the nineteenth century. It couldn’t be right. Again he took the book, sealed it and stamped my passport, telling me that I had to show it when I left the country. Otherwise…?

Janis Joplin

The people we met in Czechoslowakia were curious, if we had records of Janis Joplin, or books, perhaps Kafka, forbidden in his own country! I showed what we had in the car but I couldn’t leave the articles of the Bertrand Russell Conference with them. A bizarre situation. To seduce my students to read, I needed to motivate them, and here: the opposite.

The 70s in the West were the beginning of mass consumption on a scale as never seen before. After forty years, the grapes seemed to be getting a bit sour. Overconsumption equals high debts. Banks, states and individual consumers, all have been spending more than they own. Of those three, only the citizens who also are consumers have to pay the extra taxes for what all three have been spending at the expense of the future: their own and everyone else’s.