In her honor

My mother died while we were travelling through the USA. It happened one day after the weekly call to the family at home. Father couldn’t reach us on time. Not to be present at the funeral of a parent, child or dear friend, makes it difficult to say goodbye. We make this journey in her honor.

A first impression

A guesthouse in Negombo was our first stop. We didn’t want to stay in Colombo, a city of 1.6 million; today 2.3 million. The rooster and crows near the guesthouse woke us in the early morning with creaking sounds. Their noise made the first days even more peaceful. The people speak friendly and softly. Descriptions of Sri Lanka as paradise on earth seem to be proper. As in some other Asian countries, women behave with so much grace, friendliness and ease that associations with paradise come naturally. In the absence of a belief in Fallen Man, one develops a natural trust in the goodness of human nature.

A Buddhist monk

We travel with seven: the oldest child eighteen, the youngest six months. Travelling by public transport with seven people is an event, especially in crowded situations. So it happens in a bus, loaded with Buddhist pilgrims and some monks on their way to Kateragama, that there is no place to sit. I ask one of the monks whether mother and child might sit on his chair. “No”, that wasn’t possible because “the other monk wasn’t supposed to sit next to a woman.” I said: “I don’t think that the rule is an appropriate interpretation of the intention of the Buddha in this situation”, but my remark was of no avail. As usual, rules prove to be stronger than the voice of right intention. But I insisted, and said: “Her name is Tara, the tear of the Buddha, the goddess of compassion”. The monk smiled, stretched out his arms to receive the baby and let her sit on his lab. Everybody happy.

Talaimannar

Before exploring the island, we wanted to visit Tamil Nadu, a state in the South of India with 52 million inhabitants, and a language close to Sanskrit. The ferry goes from Talaimannar to Rameshwaram. In Talaimannar we saw crying Tamil men and women, saying goodbye to each other. A lot of police. It didn’t look good. These were the first signs of a bloody civil war to come. More signs would follow. The story of Sri Lanka as God’s Paradise on Earth showed its first cracks, a reminder of the remark by Nasr Abu Zayd that all religions are what men make of it.

Rameshwaram

Arriving in Rameshwaram was an arrival in a different world, not only in a different place, but in another cosmos. The energy, the heat, the noise was astonishing.

The Tamil belong to the Dravidian people, a race in their own rights with ethno-linguistic ethnicities, tracing their culture beyond memory, no different than Sri Lanka’s history of 125.000 years and more. The daily procession around the Great Menakshi Temple in Madurai with gongs and elephants drawing the Golden Calf around the building, inspired Judith to say: “My Jewish ancestors got punished for venerating the Golden Calf, and here they honor it in all its glory”. I couldn’t help but think that both Calf and Capital begin with ‘C’, except that the Calf participates in a world view that stems from a matriarchal culture in which everything in nature is holy and worthy of respect, while capital loves only itself. The choice between calf and capital can’t be difficult.

Shivalingam

During the journey southward to visit friends in their house near the Indian Ocean, we were struck by the shivalingams in temples and along roads, representing female and male principles such as vagina and penis. Here we found a religion that goes straight to the essence of human life by putting sexuality and Eros, the creative force of the cosmos and the beginning of human life, in the center of their rituals and piety. Not only in temples, also in the backroom of a shop one can see how men and women venerate the lingam by placing fresh flowers and burning incense in front of it. At the same time, there were signs pointing in a different direction, such as the Ayodhya incidents or the manifestations of the political party BHP. Also the crude repression of women and the caste system with its marriage rules that may ruin a family with only daughters. It took me many years before I began to understand how many ‘contradictions’ were present in this huge country where millions dream in their vernacular language but speak English in the Indian parliament, to bridge the gap between their indigenous languages.

Matriarchal and patriarchal cultures

The journey to the south, the heartland of the Dravidian culture, harboring the traces of an ancient matriarchal culture, stimulated me to visit India many times, hoping to find some answers to the complex question of the transition of a matriarchal culture to a patriarchal one. Intuitively, I felt that the difference between matriarchal and patriarchal cultures could be of a similar importance as the discovery in my dream of nomadic and sedentary experiences of life. Perhaps there were links between both. Could it be that the repression and gradual disappearance of tribal cultures were part of the transformation of matriarchal societies into primarily patriarchal ones? The question is of importance, not only for Indian or other Asian cultures, but also for other continents and Europe. The Greek Olympus with Zeus and his women; the stories about the ancient Goddesses; the Eleusinian mystery cults; Athena with her helmet: this ‘Olympic carnival’ of gods and goddesses shows all the signs of a transition of prehistoric matriarchal systems toward patriarchal ones.

The Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is the geological result of the clash between India and the Asian continent 55 million years ago, resulting in the Himalaya and Tibetan plateau. India appears to be the place to study the clash and subsequent transition from a matriarchal into a patriarchal society. The transition of an earth-bound religion with the female as the creative force toward a sky-bound veneration of the male gods or the God of the sky as the almighty One, is crucial for the understanding how religions and social systems interact. Judaism, Christianity and Islam are patriarchal religions, with an interesting exception. The ancient matrilineal social system which is still found in small pockets in the south and the northeast of India, is also present in the Jewish tradition. Being Jewish depends on the matrilineal descent, although rabbinical authorities can override the rule.

However, patriarchal social systems are not the exclusive domain of monotheistic traditions.

Patriarchal social systems, an invention by men, not by religions.

The transition in India from a matriarchal religious and social system toward a patriarchal one has been the outcome of a long struggle between the Aryan culture of the North and the Dravidian cultures in the South. The Aryan caste system is highly hierarchical: the apex are the Brahmins, priests and scholars. They enjoy the highest power, being in control of the interpretation of cosmos and life. A Brahmin could have sex with any woman he wanted. The Kshatriya are the warriors and rulers, acting in close cooperation with the Brahmins, favoring each other’s position. The Vaishya, traders and merchants, and the Shudra, servants and workers, are the third and fourth caste. Dalits form the group of the untouchables.

The Dravidian religions as well as the Shaivites, Tantrics, Shaktas and Buddhists rejected the Aryan caste system. The increasing power of the Aryan caste system may well explain why Buddhism disappeared nearly completely from its homeland, the Indian subcontinent.

Independent, modern India and its traditions.

It is a striking example of the Indian Constitution after India’s Independence in 1947 that in 1997 K.R. Narayan was elected as the first Dalit President of India. The Indian Constitution rejects the caste system but it hasn’t the power to alter its age-old beliefs and customs, especially when these are linked to power and control mechanisms. Also the Constitution’s acceptance of secular humanism as foundation for the freedom of its many religions and life-stances, is of great importance. But that doesn’t end the struggle between religious aspirations with fundamentalist overtones. Ayodhya is such an example.

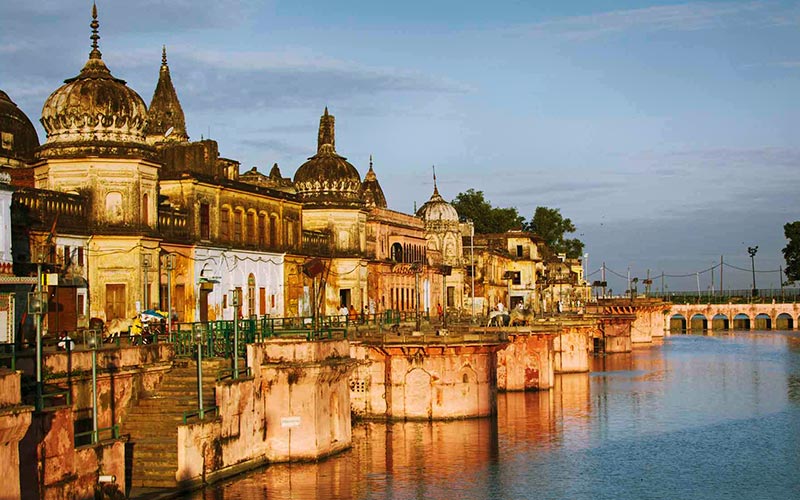

Ayodhya: how truth follows power

Travelling through India, our train halted in Ayodhya. There weren’t many people at the station. The weather was rainy, nothing remarkable except the fact that Ayodhya was world news. Hindu and Muslims were clashing about the question whose temple or mosque was there earlier. The outcome of serious archaeological research that there had never been a temple of Ram on the spot of the mosque, wasn’t enough evidence. A Hindu leader responded: when millions of Hindu believe that there was a temple in former times, then it stood there in former times. With other words: truth follows power; facts don’t count. Nazism and fascism, Leninism, Stalinism and Maoism uphold a similar approach to the past. It is also the belief of every nation that rewrites its history, or realizes its aims and rights by establishing facts on the ground. It is the story of Mars, not hindered by anything else than another Mars. It is the message of Sartre’s existentialism that the essence follows the actions. It is the motto of an unbridled capitalism that preaches creative destruction. All modern ideologies share the belief in this kind of activism.

Mahatma Gandhi

‘How truth follows power’ stands in stark contrast to the philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi, still a living presence among Indians. Walking with Colette in Madras in 1996, the year Madras’ name changed to Chennai, we strolled for a while side by side with an empty, very long farmer’s cart, drawn by two oxen, with two drivers. We were both wearing white clothes. The cart was covered with the leftovers from dry hay. I made a gesture to the drivers and their cart. They laughed and invited us to take a seat. So we did. What happened, was amazing. People in buses and on bikes, waved their hands and called Gandhi, Gandhi! We greeted them back, realizing that my round glasses, bald head and white clothes reminded them of Gandhi. Everybody was laughing and cheering.

Hindu fundamentalism, colonialism and Western ideologies

The example of Ayodhya illustrates how fundamentalism can hit even a great democracy like India. Early morning in New Delhi, Gaia and I are asleep in a hotel on the 15th floor. I am awakened by the beating of drums. Men are marching in the street along our hotel. Their footsteps sound like those of soldiers; the beating is slow and threatening. They want everyone to know: here we are! Their marching and drumming radiate sheer force, as if preparing themselves for war whenever the opportunity presents itself. Later that day we heard that members of the BHP were marching through the streets. Once more a sign at the wall how extremism manifests itself even in the heartland of Hinduism that has the name of embracing whatever exists by giving it a sacred status, as we saw on the market with a new fruit. But Hinduism as such doesn’t exist. Any so-called essentialist interpretation of a religion is overstretching its multiple origins and messages. From time to time there are prophets, messiahs or teachers with an enlightening message, showing deep insights, or with an all-embracing perspective of justice and love. What follows is the interpretation and re-interpretation by powerful men such as the Brahmin, applying the Laws of Manu first of all to their own benefit as happens in all institutions, sacred or profane.

The history of the BHP-march goes back to the thirties: “…before the British were forced to leave in 1947, there were already right wing Hindu movements based upon the brown shirts in Germany. People were borrowing ideologies from the Hitler Youth. We had communist parties in pre-partitioning India as well as these right wing fascists movements which came up through organizations like the BHP, a Hindu fundamentalist organization.” ![]() Islam Unknown, Asma Barlas.

Islam Unknown, Asma Barlas.

Aryans

Aryans, to this day, continue to seek ways to dominate India. Under the heading Aryan patriarchal society Ray Harris mentions how the process began with the Muslims – the Mughal Empire from 1526 till 1857, “but the British pushed it with force. The Arya complied happily because it gave them more power. The reality is that the process of Aryanization of India went slowly…strongest in the North West; weak in the South and East. The British adopted the Laws of Manu as guide for all the Hindu, thus legitimizing Brahmin authority…The Aryan caste system resembled the British class system. Many Aryans became Anglophiles, even when they supported independence. Adopting a Victorian moral code, the Aryan conservative is extremely prudish.”

The film Raja Hindustani, released July 13, 2010, caused an uproar because their lips kissed for a too long time. A number of mayors have imposed strict codes on public affection reminiscent of fundamentalist Islam.

Harris concludes that the condition of women under the Arya is brutal and dehumanizing.

“I would have no hesitation in saying that of all the religions the Arya treat women the worst,” adding that “the Arya have been involved in the systematic and sinister attempt to rewrite Indian history” and that “The Indian media is firmly controlled in the name of public morality, but it is really in the name of Aryan patriarchal control.”

Meditation in front of a tree

My first experiences in the South of India were different from those I describe above. Staying in the house of friends near the coast in Tamil Nadu, we were invited to the house of the president of the Congress Party of Tamil Nadu. He and his wife lived conform the old traditions. Early afternoon, our host invited me to go for a walk. It proved to be his walking meditation. Standing in front of a huge tree, he spoke the words: all the leaves of this tree are different. I was struck by his utterance. Only then I understood why he had asked me for a walk. If a politician sees the differences between thousands of leaves on the ‘same’ tree, he also sees the differences among people. This happened during the summer of 1980.

The Atheist Centre, Vijayawada, India

An invitation to present a publication by the late Gora, the founder of The Atheist Centre for social change, brought me in 1992 with my sons David and Job to Vijayawada, not far from Madras.

Preparing my speech, there was a sudden tumult at the arrival of Buta Singh, a Sikh, minister of interior affairs of the Government of India, surrounded by numerous bodyguards. The Sikhs who wanted an independent homeland Khalistan, used violent means to reach their aim. They put a price on the head of Buta Singh.

Gora and Mahatma Gandhi

Gora wrote about his encounter with Mahatma Gandhi. Inspired by their relationship in which not their different beliefs but the fruits of their actions are center-stage, I spoke about the relation between means and aims, arguing that the means one uses to reach a certain aim, tell more about the content of the aim than the aim itself does. My sons on the second row saw Buta Singh making notes.

After presenting the first copy of the publication to him, he asked me whether we planned to visit New Delhi. The answer was ‘yes’. ‘In that case, please, come to visit me’, and he handed me his card. So we did, a few weeks later.

A visit to Buta Singh

New Delhi. The villa was well guarded. Heavily armed guards let us in. People were waiting, sitting on a bench along the corridor to his room. Common people, all wanting to talk to the minister, the one with responsibility for the safety of a billion people. A scene unimaginable in Holland.

He showed us his latest New Year card that presented all the religions of this immense country within a circle. He said that each of them manifests a special view that adds to the richness of life.

David, who recently founded a special funeral centre in Amsterdam, asked him whether it was allowed to transport a dead person from The Netherlands to Varanassi for a cremation. ‘Yes, except in case of a criminal past or aids’. From time to time, a guard opened and closed the door. We talked for at least thirty minutes: from an ethical point of view, the means are more important than the aims; from an aesthetic perspective, form is more important than content or meaning. It was a privilege to talk with this great man, a Sikh whose belief, i.e. Sikhism, has its sources in Hinduism and Islam.

Varanassi and Madurai

From New Delhi we travelled to Varanassi, the holiest place for Hindu. After the cremation of their loved ones, people throw the ashes in the Ganges. The first born son has the ritual task to light the wood for the cremation of his parents, and to push the arms or legs back into the fire when necessary. To see all these burning piles of wood with the bodies amidst of flames, while men are throwing their nets in the Ganges hoping to find some gold or gems, surpasses any theatrical performance, especially when it gets dark. This is, in fact, India’s secret: night and day, sometimes more at night than at day-time because of the heat, lots of people in the streets and the squares, doing what they are doing. Like the man sleeping, his head on an oil barrel, the feet on another one, stiff as a plank.

Hypnosis

After seeing this man in Madurai, I decided to follow a course in hypnosis, wanting to know whether self-hypnosis could possibly explain this phenomenon: to sleep as a plank without any support in the middle. I don’t know whether Michel Foucault visited India. I doubt it but here, in this country, the distance between the mad, the fools, the sadhus, and other religious men amidst of everyone else, is only gradual. Everyone is a mirror to someone else. In terms of public theatre by the public, India surpasses any other country that I happen to know.

Ahimsa

Mahatma Gandhi makes a distinction between the dignity of a human as person, and his acts or intentions whatever they may be. He used the distinction to support his ahimsa, i.e. non-violence strategy. Gandhi himself was killed by a fundamentalist Hindu, like prime minister Yitzhak Rabin of Israel was killed by a fundamentalist Jew. A fundamentalist of whatever background, acknowledges only one distinction: between his world view and all the other ones. His world view is Truth with a capital ‘T’. It is self-projection in its most severe form.

Islam Unknown, Nasr Abu Zayd.

Rajiv Gandhi

Suddenly, there we saw Rajiv Gandhi, Prime Minister, only a few meters away from us, walking in Varanassi, surrounded and followed by many people. I said to my sons: “This is unbelievable, any fool can kill him”. Some weeks later, exactly this happened in Tamil Nadu. A woman with flowers, a bomb under her sari, blew herself into the air with Rajiv Gandhi. The lack of support by the Indian government for the fate of the Tamils in Sri Lanka had enraged the Tamil refugees that fled Sri Lanka. Eight years before, Indira Gandhi lost her life by a gunshot of one of her own bodyguards, a Sikh, after she had ordered a shoot-out against Bhindranwale and his followers, in the most holy shrine of the Sikhs, the Harimandir Sahib complex in Amritsar. I once spent the night there on July 24, my birthday, observing the serene atmosphere and the way Sikhs approach their most holy book. Gian Piero Frassinelli and I heard the news of the killing of Indira Gandhi, the mother of Rajiv, in Amsterdam’s metro station Waterlooplein. He was amazed and enraged. I wasn’t amazed after that night in the Harimandir Sahib complex. Stepping over the boundaries of people’s most inner convictions, religious or otherwise, is dangerous. If Henry Kissinger calls national borders ‘sacred’, what to think about the sacredness of temples, churches, mosques and other holy places!

The shaving of two heads

We return to Madurai after we have spend some time in the south. Before we leave, I decide to shave my hair and beard in India, wanting a radical change in my appearance. I know the change will be for a long time, probably until my death. I don’t know that Adam, my son, has a similar plan. When the local barber visits the house to do his job, we both leave for the garden, amazed and amused to discover that we took a similar decision.

Walking in Madurai, people approach us, asking whether we are converts or pilgrims. We discover how important the distinction between a tourist and a pilgrim is, for both Hindu and Buddhists. Bald Tara, six months old, on the back of Job is greeted with the highest respect, people touching her head.

Nyanaponika

On the ferry from Rameshwaram to Talaimannar, an ex-secretary of president Mrs Sirimavo Bandaranaike approached me to say that his wife was impressed to see a white woman breastfeeding her child. She had never seen this before. The child was Tara; the mother Judith.

The couple returned from a pilgrimage after reaching the retirement age of 60. He invited me to visit the Buddhist Center in Kandy. So I did. Thanks to his mediation, I could visit Maha Thera Nyanaponika (1901-1994), a Buddhist monk, born in Germany.

I think, it is only enlarging the problem

During the visit, one is supposed to ask questions. My question was about identity, saying: ‘Thera, let’s not talk about individual identity so well known in the West. But what do you think about Atman, the greater Self’?

His answer: ‘I think, it is only enlarging the problem’.

I was astonished, not knowing whether he was joking, playing a trick on me or that he was serious. After three days, I realized that his answer referred to Atman as Brahma or World Soul. His Theravada Buddhism approaches Illumination or Enlightenment as the negation and absence of any form or substance.

Kateragama

Back in Sri Lanka, at the side of Kateragama’s river, Buddhist pilgrims standing in the river lift Tara above their heads to hand her to their neighbors until she reaches the other side of the river, and then back again to where we are. Not for one moment are we afraid. Everything happens peacefully as part of their rituals.

That night we see men and women walk, some fast, some slowly, on huge piles of burning wood, not far from the place of the tree that stems from the tree of Benares where according to tradition Buddha got enlightened. The tree, 2200 years old, is supported by many poles, with snakes in its holes. Snakes are holy in India and Sri Lanka in contrast to Europe and North Africa, where truck drivers kill them.

Eating with the right hand

India and Sri Lanka share an old tradition of eating food with the right hand, while seated on the floor or close to the floor. In Sri Lanka it happens in a simple restaurant. We are supposed to eat with the right hand after washing our hands. In Kashmir at a marriage party in grand style, to which we are invited, all guests – each time four people around a large round plate – sit on the ground and share the food using their right hand. Once in a house in Calcutta the woman served me by putting the food with her right hand into my mouth. Whether this tradition will survive the 21st century, I don’t know. I mention it because of Marco Polo’s story about South India and Sri Lanka.

Marco Polo

Returning from China in 1292, Marco Polo arrives at the Coromandel Coast of India. He writes that according to custom, ‘the king and his barons and everyone else all sit on earth’. Marco Polo asks the king why they ‘do not seat themselves more honorably.’ The king replies, ‘To sit on the earth is honorable enough, because we were made of the earth and to the earth we must return.’

The Travels also reports: ‘The climate is so hot that all men and women wear nothing but a loincloth, including the king – except his is stubbed with rubies, sapphires, emeralds and other gems. Merchants and traders abound, the king takes pride in not holding himself above the law of the land, and people travel the highways safely with their valuables in the cool of the night.’ He calls this ‘the richest and most splendid province in the world,’ one that, together with Ceylon (Sri Lanka) produces most of the pearls and gems that are to be found in the world.

Naked people

Polo’s story reminds me of images of naked men we saw along a road travelling by car on a secondary road in the direction of Bombay/Mumbai. The men were only wearing a string. Seeing our car, they disappeared into the forest nearby the road. The same happened in Sri Lanka, when we were looking at a location to the south of Colombo. Entering a large domain, we saw naked people with paint on their body. Asking our guide, he talked about them as locals still living according their old habits.

Aryan patriarchy and Dravidian matriarchy

Travelling in India brings every pilgrim and tourist, if interested, in contact with the Indian cave and temple art, deeply erotic in the spiritual and physical sense. The Buddhist ruins of the Kanheri caves just outside Mumbai with carvings of nearly nude male and female figures are one of the many examples.

The question arises what happened to this erotic culture that abounds in sexual and spiritual beauty.

The answer(s) might also shed some light on the disappearance of Buddhism in India.

Before the conquest by Aryans

For most of its history, according to Harris, India didn’t have a problem with nudity. Prior to the Muslim invasion, the overwhelming majority of women went topless, especially the lower caste and tribal women. Covering the breasts was “a privilege only afforded to the higher caste, not out of modesty but simply to enforce caste distinctions. This tradition even extended well into the Muslim era, particularly in the south. And in the more remote Hindu populations of Sri Lanka and Bali, women did not start covering up until the 20th century.” A striking example is queen Kallada who received a Dutch traveler with her breasts exposed, according to an account written in Malayalam.

The question

I ask myself the question whether the difference between matriarchal and patriarchal cultures could be of a similar importance as the discovery in my dream about nomadic and sedentary experiences of life. The answer is ‘yes’, even more so than between nomadic and sedentary cultures. Marco Polo writes about a sedentary culture, where the rule of law applies to everyone, including the king. It also exemplifies the equality between people in their nudity and their common bind with the earth, when the king answers Polo’s question why they sit on the earth.

We see here all the elements of a world view that is both democratic and earth-bound; with equality between women and men, being safe while travelling at night with their goods, and being rich. The contrast with the Aryan caste system and the British class system as their ally couldn’t be more outspoken. The gradual dominance of the patriarchal system, not only in India, but practically worldwide, has been a transformation that poses the question whether there can be an evolution in the opposite direction.

How to understand the change in power from women to men?

Part of the answer is that the transition of earth-bound religions toward sky-bound religions runs parallel to the transition of matriarchal toward patriarchal societies. To study what happened in the context of India’s ancient and recent paradigms, might be helpful to get the issues of sex and religion, nature and modernity, and the effects of capitalism’s law of unequal development, into focus.