Orientation

We began talking about a journey to the Dogon before our great odyssey in 1973. A friend of ours travelled regularly through the Sahara to Mali to visit the Dogon. His passion for their culture, masks and sculptures included, was so great that he worked for six months as an architect to be able to travel the other six months. His stories about the Sahara had stirred our imagination. One of his lessons was: in case of trouble never leave your vehicle.

Entering the Sahara, in the hamlet Reggane, Algeria, we signed ‘the book of the dead’. In case one didn’t return, the names of those who had disappeared without leaving a trace would be known. We got permission to lift a stone under which there was a little stream of clear water. We filled five containers of 20 liters each. A sign with Mali on a wooden pole was moving in the wind. From Reggane to the border with Mali was 2000 km. No other sign would follow.

I drove southwards until the evening when we got stuck in the sand. We decided to sleep and to solve the problem early morning. When it became light, there were no traces left and every guess in what direction to go was as good as any other one. The car didn’t move an inch. We realized that we had lost the common track and with the track our orientation. The children began to sing: we are sitting here but we always get out, instead of their usual song in the desert: we are sitting here and we never get out.

In case of trouble never leave your vehicle

My suggestion to start walking wasn’t accepted. I had forgotten the advice: In case of trouble never leave your vehicle. Nothing else to do than to wait and not to panic in that endless space without a horizon. Early afternoon we saw some figures walking in our direction. After less than an hour five Algerian men arrived at the white van, drank tea, entered the car and directed us in the right direction, only by moving their hand a little to the left or a little to the right. They had seen the sunlight reflecting in the air in a manner that they didn’t recognize, and decided to have a look. They saved our lives. We continued our journey through the Sahara to Tamanrasset, 2000 km south of Algiers. We spent six weeks in the great desert. It was early spring 1973 with hot days and cold, bright nights. The silence was so deep that our senses and body consciousness altered by expanding into space. Space became the dominant experience; time a modus of space. It is difficult to describe but the emptiness of the desert is so powerful that it annihilates every previous experience, sound or image. It simply cannot be compared to anything else you know or have seen. Your mind reaches the bottom, before it began to learn and to be formed by education. ‘No, not always, not in the Sahara! Preface to Michel Foucault, Freedom and Knowledge, a hitherto unpublished interview.

From the day we got lost and were saved, orientation became a guiding idea in my life.

Entering the animist world of ancient Africa

This time, 1976, we decided to travel by plane to Bamako; from there by ‘public’ transport to Mopti and Sangha where we would meet our guides Amadinge and Dolo Asegrama, and the men who would carry our luggage. There wasn’t any road left other than the ones for walking. Our group existed of several men and women, and six children: two sons of a colleague at the Academy of Architecture and my four children: David, Job, Adam and Gaia.

The first night of the journey to Kundo Ando, the village where we were going to stay, we slept on a cliff under overhanging rocks. The skulls of the ancestors only a few hundred meters away. In the evening Amadinge, an initiate of the Dogon tribe, told us about the spirits of the ancestors. I translated his story for the children. Adam looked at him with an attention in his eyes that told us that the spirits were equally alive for him as for Amadinge himself. We had entered the animist world of ancient Africa.

The ancestors are there

1976, December 15. Today we walked to Kundo Goumon, one hour to the north from our village Kundo Ando. The journey went through crevices, along steep rocks and some villages, a journey that gives more energy than it takes. That feeling surprises me each time: there is something present in the Dogon region that seems to be the opposite of everything we are used to. Kundo Goumon is an old abandoned Dogon village with only two old women and a few children living there. The water comes from a hole in a rocky wall. The villagers don’t live in a Dogon hut but in a hole. The Tellem constructions stand high above the village on a ledge two, three meter wide as magic signs of a vanished people. The people living here maintain contact with the ancestors: it’s their reason of existence. The ancestors are there: their bones and pots the witnesses. The men have left in search of work.

Education

1976, December 30. The purity and harmony of these Dogon impress me like equally evident characteristics as egoism and lust for power in Western societies. If the Dogon don’t want to speak the truth, they don’t lie but foster it as a secret by not talking about it. We usually prefer the lie. The adults teach the little children to give. An old woman with flat breasts, in fact two hanging skins, holds her hands up in front of our nude Gaia, two years old, and asks her to give something but with the clear intention not to keep it for herself. Undisturbed, Gaia continues to eat her mango but the woman is patient. Finally Gaia drops the wet pit of the mango into the hands of the woman. The woman accepts it happily, lifts her hands to the sky as if she asks a blessing for this gesture, and returns the pit to Gaia.

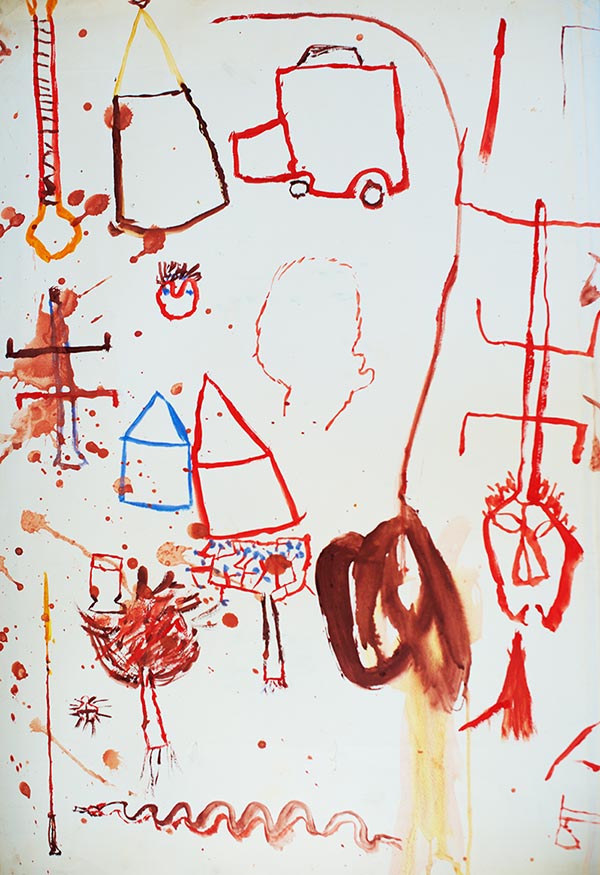

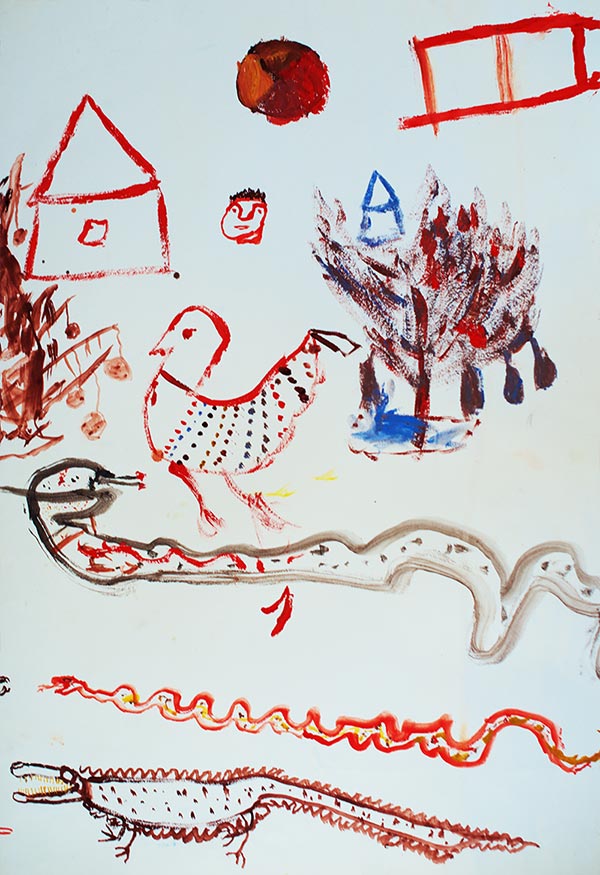

Drawings in Kundo Ando

Offering characterizes the life of an animist

1976, December 31. While I shit green between the rocks of the Falaise, the red-yellow sun rises above the plain of Upper Volta (today’s Burkina Faso), that endless plain of sand, scattered trees and fallow fields. Today there is a feast in our village. We bought two hundred kilos of millet for 10,000 FM, and two sheep for 10,000 FM. The sheep were slaughtered this morning and are being roasted now. The kids play with our balloons. The sun gets hot and the sand begins to burn under my feet. The men bring the konyo (beer that they brewed from millet) from all the corners of the village to the fig tree in the centre of the village. It took days to brew the beer in tall earthenware pots above fires. We hope to film the people when they start dancing this afternoon. An old man pours some konyo on a stone near the fig tree. Offering characterizes the life of an animist. To give precedes the getting like a baby’s shitting during birth precedes its drinking, and also dying often goes together with the last offering of the body.

Always a dialogue

1977, January 1. Saturday morning. Everybody happy? The Italian who gave Alma and me a lift from Napoli to Rome in 1963, asked each time before we entered his car again: everybody happy?

Last night we danced for hours during ‘our’ New Year’s eve, turning around in circles around the tam-tam of some boys which themselves moved also all the time. Alternatively, the song of a man from the male group with the voice of a boy, man and woman at once, got a counter song from and by the group. I danced behind William who danced behind a boy. The women stood apart, intimately together, a solid group, in which not only all the good sides but also the weak sides come together, as Judith briefly summarized their encounter.

An old man was dancing and laughed intensely happy. He was enlightened and liberated – pure joy about the dancing people and the intense integration of us all. His talk with the Ammir was impressive by the gestures, the physical gestures of his thoughts, in which he convincingly communicated: “let the people dance, as long as they are happy to do so”. In this village, people convince each other; they don’t win and they don’t lose; they talk in the same way as they produce their rhythms together. It’s always a dialogue.

The moon disappeared behind the high rock wall. It was about 01.30 h. …the opposite of sunrise, but it remained light. The clouds float in endless movements along the firmament; the stars shine with great intensity, especially Venus. I see the stars transform into great metal hexagrams hanging motionless in the sky as static, surrealistic Dali paintings. I close my eyes and wait. When I open my eyes, the metal balls have disappeared; the stars shine again in all their simplicity, as if we are shepherds. We lay on our dusty mattresses in the sand between the walls of clay and stones with the sky above us. Gaia wakes up: “Moontje, moontje”, she calls and plays with the right-angled flat cover of the chess game, as if she experiences the wood as love.

We are also AMMA

1977, January 3. Yesterday we walked with Gaia on our back to Yougoudougourou and Yougou-na, a heavy journey through the plain and mountains. Yougoudougourou is the sacred centre of the Dogon, the origin of their history in this region along the 200 kilometers long rock wall where the Tellem lived before the Dogon entered the region. It is situated on a high mountain in the Falaise, difficult to reach. Lots of houses are in a bad state. There is nothing that looks like a sacred place. Only by sitting on a stone or by making pictures do we discover that nearly everything is sacred. The Dogon are religious in heart and soul. Their sacrifice on a stone for AMMA transforms the stone into AMMA, and gives the stone its inner force. AMMA is identical to Air, Water, Fire and Earth. When I said to Amadinge that we, humans, are also air, water, fire and earth, he responded literally: we are also AMMA.

The animism of the Dogon is only visible in an indirect manner: in their behavior toward each other; the souls of the ancestors and Tellem; the respect for AMMA; the rhythms on the drums; the passionate, one minute dance of the women; the dancing man who throws himself in full length on the ground and jumps on his hands and feet, to rise again to dance further.

Life is good, but death belongs to it

The Dogon greet each other in long, singing sentences: poi, poi, u sewo, sewo. Especially from the mouth of the women it sounds like music and poetry. Their greetings are expressions of love and modesty, they testify of a great respect for life. During the funeral ceremonies which – with intermezzo’s – last seven days and nights, they sing: Life is good, but death belongs to it. The Dogon live in love and fear with their dead of which the souls continue to live in the ‘waggon’, the Ginna. Life is one great cycle, with an afterlife that resembles the life before. If one dies as a good human, life after death is identical to the moment of dying. When one dies as a bad human, the activities after death will show that. This perspective explains the fear for black magic, as everywhere on earth where one experiences the cycle of the living, the dead and the yet to be born.

Their huts are small; their imagination limitless

1977, January 5. During sunrise I went outside to lay on a rock. The sun, hidden by mist, only became visible after it rose above the horizon. While I was laying down like a dog, happily and quietly, I realized how good it is to lay down wherever one wants, as dogs, cats, sheep, goats and chickens do wherever they like. Nobody here is surprised. Everyone does it. My body walks around as if it has regained its contact with the earth: quiet and content to walk without a direction or goal. Kundo Ando became my sacred spot where I would like to be buried as I would like to be buried at the farm. But there is a difference. The farm is my sacred place with links to the family and neighbors, while here the whole environment and all people foster the link with their dead and the cosmos. Their space stretches itself far beyond the visible limits. Their huts are small; their imagination limitless.